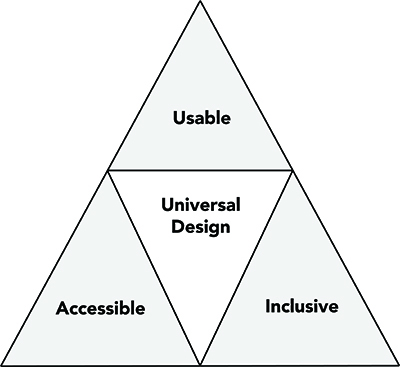

The Universal Design

The Concept

Over time, the terms «disabled» or «handicapped» have contributed to the alienation of certain sectors of society. It is essential to create spaces in which all people, regardless of their abilities, can feel like an integral part of the community, recognizing that everyone has diverse abilities. As architects and interior designers, our responsibility is not limited to designing spaces for individuals considered «normal»; we must also consider those with different abilities, including those who use wheelchairs or are blind, so that they can fully enjoy the environments we offer them.

My goal in this project is to ensure that people who are blind or have reduced mobility can participate on equal terms in all aspects of everyday life. To achieve this, my job is to adapt both the interior and the exterior of the buildings, ensuring that every corner is accessible and cozy. This approach involves not only the removal of physical barriers, but also the creation of an environment that promotes dignity and respect for all people.

The research I have conducted in this field has provided me with a deeper understanding of the difficulties and challenges faced by people with disabilities. I have been able to identify the architectural and social barriers that perpetuate isolation, as well as the innovative solutions that can be implemented to overcome them. This learning process has given me valuable ideas and tools that will allow me to close the isolation gap and foster an environment where equal opportunities, access and rights are a reality for everyone.

In developing this project, I aspire to create a space that is not only functional, but also reflects a genuine commitment to inclusion. It is essential that every design we undertake is aimed at building a future where all people, regardless of whether they have a disability, can enjoy an environment that allows them to fully develop and actively participate in society. Ultimately, our goal should be to contribute to building a more just community, where diversity is celebrated and every individual has the opportunity to thrive.

Definition of a person with a disability

The Law defines a person with a disability as one who has one or more permanent physical, sensory, mental or intellectual deficiencies, who, when interacting with various attitudinal and environmental barriers, does not exercise or may have been prevented from exercising his rights and his full and effective inclusion in society on equal terms with others. This definition includes people declared judicially incapable, that is, interdicts, as well as people with disabilities who are not subject to interdiction, since they allow free will and the ability to discern.

What is Inclusive Architecture?

Inclusive architecture refers to any space that can be seamlessly used by all user groups, including those with a disability. The main objective of any piece of inclusive architecture is to make a space as barrier free and convenient as possible. Removing the traditional barriers that exist in certain architectural practices should allow everyone to participate in everyday activities equally and independently. Accessible or inclusive architecture considers the challenges faced by individuals with disabilities in regards to the environments they interact with. Inclusive architecture designs spaces, buildings, or communities that are accessible to everyone, without posing safety risks or requiring extra effort. The goal is to make sure everyone can enter a space or building and use it fully.

About UD

When talking about accessibility in architecture, codes set the minimum requirements, while design determines the overall look of the building’s roof. While there are many rules to follow, making spaces inclusive is more than just obeying guidelines. Designing requires a good understanding of different people and their needs. We need to think about how our designs will be used by a variety of people with different bodies, abilities, and conditions. This includes not just the usual users, but also people with disabilities, pregnant women, those who use assistive devices, and people of all ages and body types.

It is important to make sure that everyone feels included in the design of environments. The Principles of Universal Design were created in 1997 by the North Carolina State University School of Design and led by Ronald L. Mace provides a new way of looking at things in this situation.

This method has an impact on various areas of design like buildings, products, and communication. Applied to architecture, universal design promotes the development of spaces that are usable by all, reducing the necessity for adjustments or custom features.

Characteristics of accessible or inclusive architecture

RULE 1:

Floors without irregularities: that are non-slip to favor their safety and displacement.

Pavilion in Santa Clara Park, Argentina.

RULE 2:

Installation of accessories: such as ramps, fasteners, support railings or mobile platforms, which allow the use of the spaces with greater safety.

Public transport in Barcelona, Spain.

RULE 3:

Large spaces in all rooms: so that tools such as wheelchairs can be used and they can move without difficulty.

Bronx Children’s Museum. United State of America.

RULE 4:

Use of materials, textures and colors in spaces: this is vital signage for people with visual impairments so that they can guide themselves through spaces independently.

Qkids English Center, CHINA.

RULE 5:

Integration of inclusive languages: Braille and sign language can be integrated into spaces such as elevators or audiovisual messages respectively.

Elevator Jamb Number Sign — Braille

Principles of Universal Design

Knowing the difficulties that a person with different abilities faces, is the beginning to the solution of the problem. Universal design tries to solve these challenges of everyday life that disabled people face every day. And as architects, we must know what are the principles that apply to the interior of buildings.

Tongzhou SINLOON Canal Creative District, China

Principle 1: Equitable Use

The spatial configuration of buildings can lead to significant differentiations with a profound impact. For example, in some cases, the main entrance and the accessible door are not the same, which creates an uneven user experience. Even so, these arrangements can result in a functional separation that, while sometimes addressing specific design needs, poses challenges regarding inclusiveness and flow within the built environment.

The objective is to guarantee equal access to all resources, such as work areas, bathrooms and auditoriums. Whenever possible, access should be equal for everyone. If this is not feasible, the hierarchy should be equivalent. Differentiation should be avoided to ensure that all isoptic visibility, communication, privacy and protection are provided equally. In addition, the design must be attractive and coherent, demonstrating a genuine integration of all the elements.

Yoyogi Fukamachi Mini Park Toilet, Japan.

Yoyogi Fukamachi Mini Park Toilet, JAPAN. View from the street.

Glass exterior reveals the facility is empty, making it safe for use at night.

Yoyogi Fukamachi Mini Park Toilet, JAPAN. The glass becomes opaque when locked.

Toilet when the glass is transparent (inside view). Multipurpose toilet.

Braille blocks leading to the multipurpose toilet.

Principle 2: Flexibility in Use

Every individual perceives the constructed surroundings in their own distinct manner. Hence, it is crucial to design with versatility in consideration to allow buildings and interior areas to cater to various functions and suit personal choices. Moreover, the wide variety of products and systems on offer enhances our capacity to tailor these areas, enabling more accurate and customized setups. The environments we create should facilitate interactions that align with individual requirements and schedules.

It is essential to keep in mind that individuals vary in their walking speeds, strengths, and heights. This consciousness and flexibility aid us in connecting more effectively with our surroundings. In this way, the areas and items we utilize can boost our skills and enhance our everyday interactions.

Rita Lee Park — Legacy of the Olympic Park. United State of America.

Principle 3: Simple and Intuitive Use

«The use of the design is easy to understand, regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge, language skills or current concentration level.»

Simplicity is crucial in architecture, but achieving it takes significant effort. This principle emphasizes creating a spatial environment that is easy to understand, going beyond just aesthetics. In order to create uncomplicated and user-friendly spaces, it is crucial to eliminate unnecessary complications. The area, along with the informative components and furniture, should be well-arranged to indicate its purpose clearly. These ideas make it easier to navigate and interact with surroundings, particularly for individuals with intellectual disabilities.

Inclusive Education Center, United State of America

Principle 4: Perceptible Information

«The design communicates the necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of the environmental conditions or the user’s sensory capabilities.»

Perceptible information seeks to enhance spatial understanding through sensory design. It utilizes auditory signals, tactile surfaces, pictograms, and colors to guide, instruct, or alert users. This principle emphasizes using diverse communication methods, like visual, verbal, and tactile language, to present information redundantly through different senses. This strategy ensures readability regardless of environmental conditions or individual sensory abilities. Contrasting colors and textures play a critical role in facilitating easy navigation and comprehension. Moreover, the space should accommodate various assistive devices, such as hearing loops, to boost usability and environmental understanding.

Narita International Airport Terminal 3 / Nikken Sekkei + Ryohin Keikaku + PARTY. Imagen © Kenta Hasegawa

Principle 5: Tolerance for Error

«The design minimizes the dangers and adverse consequences of accidental or unintentional actions.»

While our designs are not intended to create unsafe spaces, certain conditions may still pose potential challenges. Thus, employing the principle of error tolerance involves arranging elements so that frequently used ones are easily accessible, while isolating those that pose risks. It’s also important to avoid actions that demand constant monitoring by others. This strategy is particularly important for features like light switches, open circulation areas such as corridors and ramps, swimming pools, stairways, and elevated locations like balconies.

West Lafayette Wellness Center, United States. Swiming pool for people in wheelchairs.

Principle 6: Low Physical Effort

«The design can be used efficiently, comfortably and with minimal fatigue.»

Our interaction with the environment largely hinges on our physical capabilities. Therefore, a poorly designed interface can act as a hindrance. To enable smoother interactions, designs should encourage a neutral body posture, demand minimal effort, reduce repetitive motions, and minimize prolonged exertion. This strategy ensures activities are performed with minimal strain, fostering the user’s health and well-being.

Minimizing physical effort can be accomplished by creating spaces with few level changes and gentle inclines, using ergonomic furniture, fitting lever handles on doors and faucets, installing touchless switches for lighting, and integrating mechanical circulation elements like elevators and escalators.

Principle 7: Appropriate Size and Space for Approach and Use

Given that each individual possesses unique characteristics and needs, our requirements for range and mobility can differ significantly. Neufert’s work on standardizing architectural dimensions highlights this point, offering vital anthropometric references, especially for wheelchair users. This research has paved the way for expanding our approach to accommodate a variety of conditions, body types, and heights.

For effective interaction, several factors must be considered, such as ensuring a clear line of sight to relevant elements for both seated and standing users, and enabling access to components from either position. Additionally, designs at a smaller scale should account for variations in hand size and grip strength, and provide appropriate conditions for assistive devices.

These considerations help all users engage with their environment comfortably and accessibly.

Casavera / gon architects. Imagen © Imagen Subliminal (Miguel de Guzmán + Rocío Romero)

ADA National Network. Learn About ADA [Article]. ADA National Network. (URL: https://adata.org/learn-about-ada). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

ADA National Network. Planning Guide: Making Temporary Events Accessible for People with Disabilities [Guide]. ADA National Network. (URL: https://adata.org/guide/planning-guide-making-temporary-events-accessible-people-disabilities). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

Ciudad Accesible. ¿Qué es el diseño universal? [Article]. Ciudad Accesible. (URL: https://www.ciudadaccesible.cl/que-es-el-diseno-universal/). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

Creative Crews. Classroom Makeover for the Blind [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: https://www.archdaily.com/918942/classroom-makeover-for-the-blind-creative-crews#). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

Creative Crews. Cómo los 7 principios del diseño universal ayudan a crear una mejor arquitectura [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: https://www.archdaily.mx/mx/1019754/como-los-7-principios-del-diseno-universal-ayudan-a-crear-una-mejor-arquitectura). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

Creative Crews. Sala de aprendizaje para ciegos [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: Las presentaciones son herramientas de comunicación que se pueden usar en exposiciones, conferencias, discursos, informes y más.). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

Nora Libertun de Duren. Espacios públicos para personas con discapacidad, niños y mayores [Report]. (PDF, pages 138-144). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

Sealab. School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: Sealab. School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: https://www.archdaily.com/984721/school-for-blind-and-visually-impaired-children-sealab). Viewed: 15.11.2024.). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

Tokyo Toilet Project. Yoyogi Fukamachi Mini Park [Article]. Tokyo Toilet. (URL: Sealab. School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: https://www.archdaily.com/984721/school-for-blind-and-visually-impaired-children-sealab). Viewed: 15.11.2024.). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

ArchDaily. Bronx Children’s Museum [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: Sealab. School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: https://www.archdaily.com/984721/school-for-blind-and-visually-impaired-children-sealab). Viewed: 15.11.2024.). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

ArchDaily. Classroom Makeover for the Blind [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: Sealab. School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: https://www.archdaily.com/984721/school-for-blind-and-visually-impaired-children-sealab). Viewed: 15.11.2024.). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

ArchDaily. Cómo guiar a las personas en espacios arquitectónicos con pavimentos táctiles [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: Sealab. School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: https://www.archdaily.com/984721/school-for-blind-and-visually-impaired-children-sealab). Viewed: 15.11.2024.). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

ArchDaily. Pabellón en Parque Santa Clara [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: Sealab. School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: https://www.archdaily.com/984721/school-for-blind-and-visually-impaired-children-sealab). Viewed: 15.11.2024.). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

ArchDaily. Qkids English Center [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: Sealab. School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: https://www.archdaily.com/984721/school-for-blind-and-visually-impaired-children-sealab). Viewed: 15.11.2024.). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

ArchDaily. School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: Sealab. School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: https://www.archdaily.com/984721/school-for-blind-and-visually-impaired-children-sealab). Viewed: 15.11.2024.). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

ArchDaily. West Lafayette Wellness Center [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: Sealab. School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: https://www.archdaily.com/984721/school-for-blind-and-visually-impaired-children-sealab). Viewed: 15.11.2024.). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

Come On Barcelona. Barcelona na Kolyaskakh [Article]. Come On Barcelona. (URL: Sealab. School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: https://www.archdaily.com/984721/school-for-blind-and-visually-impaired-children-sealab). Viewed: 15.11.2024.). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

Encrypted TBN. Image [Image]. (URL: Sealab. School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: https://www.archdaily.com/984721/school-for-blind-and-visually-impaired-children-sealab). Viewed: 15.11.2024.). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

Gooood. Publi City Tongzhou: Sinloon Canal Creative District [Article]. Gooood. (URL: Sealab. School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: https://www.archdaily.com/984721/school-for-blind-and-visually-impaired-children-sealab). Viewed: 15.11.2024.). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

Link Springer. Article on MRS [Article]. Springer. (URL: Sealab. School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: https://www.archdaily.com/984721/school-for-blind-and-visually-impaired-children-sealab). Viewed: 15.11.2024.). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

UDD. Arquitectura analizará la accesibilidad universal [Article]. UDD. (URL: Sealab. School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: https://www.archdaily.com/984721/school-for-blind-and-visually-impaired-children-sealab). Viewed: 15.11.2024.). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

Tokyo Toilet Project. Yoyogi Fukamachi Mini Park [Article]. Tokyo Toilet. (URL: Sealab. School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: https://www.archdaily.com/984721/school-for-blind-and-visually-impaired-children-sealab). Viewed: 15.11.2024.). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

Officesign Company. ADA Braille Elevator Jamb Number Sign [Article]. Officesign Company. (URL: Sealab. School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: https://www.archdaily.com/984721/school-for-blind-and-visually-impaired-children-sealab). Viewed: 15.11.2024.). Viewed: 15.11.2024.

Skillman. City of West Lafayette Wellness Center [Project]. Skillman. (URL: Sealab. School for Blind and Visually Impaired Children [Article]. ArchDaily. (URL: https://www.archdaily.com/984721/school-for-blind-and-visually-impaired-children-sealab). Viewed: 15.11.2024.). Viewed: 15.11.2024