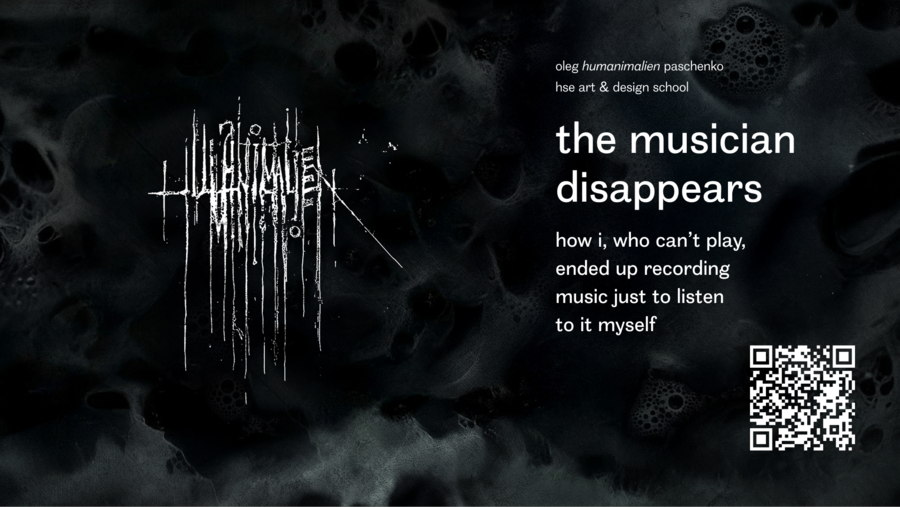

The Musician Disappears

The Musician Disappears: How I, Who Can’t Play, Ended Up Recording Music Just to Listen to It Myself

Talk at the conference «Non-Human Sounds: The Music Industry vs. AI» at HSE Creative Hub, December 4, 2025.

At first everything I wrote and did, I did for myself, because I was absolutely sure nobody would like it at all. So I didn’t give the first originals to anyone: I was ashamed that I couldn’t really play and that, strictly speaking, it wasn’t even rock. But I liked listening to it myself. I’d put it on and dance to what I’d made. — Egor Letov

I have no musical education.

I don’t play anything — unless you count a six-string acoustic guitar I last saw about twenty years ago. I don’t read music. I have no idea what the abbreviations in chord symbols mean, or how exactly the Phrygian mode differs from the harmonic minor.

What I do have is a lifetime case of musical gluttony. I listen to music as if it were my job, devouring it in industrial quantities. At some point AI tools — first and foremost Suno, later mastering plug-ins — allowed me to move from the position of a listener to that of someone who actually releases their own records.

Releases for whom? For myself.

One day I realized that nobody on earth makes music that satisfies me 100%. Something is always off: too clean, too pompous, too much compressor in the mix, lyrics that make you cringe, and so on. At some point I remembered Jean-Baptiste Emanuel Zorg from The Fifth Element as played by Gary Oldman, declaring: «If you want something done well, do it yourself.»

But in my case «myself» doesn’t mean a studio, a band, and ten years of guitar practice. It means a head, old lyrics, slightly deranged tastes, and a set of powerful tools that suddenly became available to any music glutton with a computer. That’s how my little storyline appeared: how a non-musician recorded several albums he’s not ashamed to listen to himself. And at the same time stumbled into a much larger conversation about what is happening to authorship, to the music industry, and to that very figure of «the musician» who seems to be quietly dissolving into the air.

If you tried to map my musical taste, you’d end up with something quite dark — very roughly: wherever most people feel anxious and uncomfortable, that’s where I feel interested and oddly happy.

At the center is everything to do with slowing down or, conversely, unnatural acceleration; heaviness, claustrophobia, darkness, and anxiety: black metal and post-metal, various experimental and progressive offshoots, horror film scores, gothic darkwave, dark ambient, hauntology, dark cabaret, dark country, weird Americana, neofolk and apocalyptic folk, post-industrial, dark jazz that sounds like music from a non-existent David Lynch film, and so on — all that black, murky stuff.

On the periphery: witch house, trip-hop, trap, phonk, drill, grime, the occasional strange pop record, and yes, strictly off the record, very selective Russian rap (my apologies). I like music that does something to the body; I like those genres where sound induces a psychophysical experience — more precisely, a whole spectrum of states: a constriction in the chest, vertigo, nervous twitches, sensations like the ones you get when all the air suddenly disappears from the room. (Naturally, we all know that feeling very well, don’t we?)

When I say I’m making «ideal music for myself, ” I mean experiments in mixing all these sometimes incompatible things into one black cocktail: so that it’s dark, and a little funny, and at times deeply cringey, and occasionally — almost by accident — unexpectedly beautiful.

The official blurb for our conference says that we’re discussing the influence of AI and algorithms on composition and listening practices: from AI-curated playlists to fully generative music.

My role in this little play is «non-professional armed with very powerful tools.» On the one hand, it’s democratization: a person with no musical schooling suddenly has access to a level of production that used to require a studio, live musicians, and a lot of time. On the other hand, it’s a real challenge to the industry: how do you live in a world where people like me can upload AI-assisted albums to streaming platforms?

It all started — forgive the banality — in the nineties. I had lyrics and an acoustic guitar. My friend Nikita Polyakov and I tried to record my songs. There were regular rehearsals and «recording sessions» (which in reality were just black-hole drunken nights in the kitchen: industrial «Royal» spirit cut with tap water, wild garlic on the table, all that), plus a few ambitions, dreams of a studio, even a couple of failed attempts to play electric instruments with actual people.

In hindsight it was, on the one hand, straight cargo-cult rock music; on the other hand — who knows — maybe a kind of preparation for a «real» album that would surely materialize later, once we had money, time, gear, connections, and skills.

Of course, the album never materialized. The lyrics remained in notebooks, and sometimes only in memory. A few digitized recordings live in Nikita’s personal archive, but they are, to put it mildly, a source of shame.

More than thirty years have passed since then; the nineties have turned into the era people mean when they say «give me back my ’93.» Some lyrics made it into a printed book, Uzélkovoye pis’mo, but the songs never did.

And then, suddenly, generative neural networks arrive — and finally my first more-or-less non-embarrassing album, Tachycardia. All the lyrics on it are mine; most are old, from the nineties (though there are a few newer ones). A lot of the melodies are those same ancient ones, because I was feeding Suno my archival cassette transfers as reference tracks.

Technically it’s all fairly simple. I started by cloning my voice with the help of ElevenLabs: I sang, spoke, whispered, growled, and screamed about thirty seconds of material into a fairly cheap microphone, then turned that into a Persona in Suno, which later became a timbral reference. Then I take a lyric, throw together a prompt in Suno, and explain that I want something like «raw dark jazz with post-punk and industrial flavour, slow, anxious, heavy.» I get a few versions back. At first I don’t like any of them, so I refine the prompt and regenerate; sometimes I make covers of already generated material so that certain aspects of the arrangement, intonation, and sound come out more clearly.

I delete ninety-five out of a hundred generations; the rest I rename, leaving myself notes about what each one does well or badly. In the end I’m left with four or five satisfactory variants, which I download (sometimes as full mixes, sometimes split into stems).

Then I create a multitrack project in Adobe Audition (and yes, I know «normal people» use Ableton Live or at least Apple Logic Pro), import all the audio footage, cut and paste it, and hang an FX rack on the master. That rack I gradually dialed in by trial and error and by pestering ChatGPT with questions (more on that later). For Tachycardia I used Audition’s native effects; later I graduated to Ozone 12 Advanced. Mixing and mastering are probably the two longest, most labor-intensive stages of the whole process. I can spend, say, two hours in Suno generating material — sometimes I do it on my phone in the metro on my way to work — but mastering a single track can take five to ten evenings.

In short, I ended up with a very concrete object: an album you can listen to, ignore (which is what most people will do), put on repeat (that part is mostly me), and even buy on Bandcamp — though I won’t get a single cent, because there is currently no way to withdraw Bandcamp revenue to Russia.

For me it was both painful and freeing: I had finally done what I had failed to do when I was twenty. For the record, as far as I can tell, Nikita categorically dislikes my AI music. Perhaps it distorts his own version of our shared youth, and in any case our musical tastes have diverged so radically over thirty years that they are now almost opposite. Nikita, surprise-surprise, does not like black metal. And I, in turn, don’t like a lot of things he likes.

It’s quite possible that this clash — my joy of «I finally got to hear my songs!» versus his indignation of «what have you done to our memories?!» — is already a plot for a separate bitterly confessional track. (Smile.)

The word dérive in Situationist jargon describes aimless drifting through a city, where your route is determined not by utility but by moods, smells, random encounters, accidents. The EP la dérive noire is about walking through a city as it gradually gets darker until night finally falls. (And by «night» here I mean a cover of «Black Metal» by Venom.)

A separate personal point on that release is the track «ο ακάθιστος». I wrote the text around 2009; in 2018 a composer friend and I tried to turn it into a rap track, but that never really worked. Later, in 2024, came my first full-length AI album It ain’t me, made with Udio (which at that moment was better than Suno — now it’s worse). The album turned out fairly embarrassing, although that was the first time I truly felt euphoria from a new tool and its capabilities. Still, that early version of the «Akathist» served as a reference for the remake that ended up on la dérive noire: I understood very clearly what I didn’t want anymore and how I could pull that text in a different direction.

Prototypes of the tracks «the moon in the constellation of poop» and «la dérive» were actually released back in 2018. When I hear them now I want to crawl under the table. But that shame is useful: it shows how much garbage you have to produce before anything starts to work. I didn’t even bother removing them from Bandcamp — let them hang there as a warning.

There is a certain irony in the fact that the composer I was working with in 2018 (back then under another name; since then they have transitioned, identify in the plural, and now go by legions nonbinaryrussia) has arguably become my only truly attentive and musically competent listener. He — or rather they — listen to my AI albums, send long, sometimes merciless voice messages with feedback, hear things I don’t. In a sense la dérive noire is the belated completion of that unfinished conversation we started back then.

#000000 is essentially a joke that went too far. I noticed that my head was storing a certain number of «black» songs: «Dark Eyes (Ochi chornye)», Serge Gainsbourg’s «Black Trombone,» Elvis Presley’s «Black Star,» «Black Betty, „Paint It Black,“ the russian folk song „Black Raven,“ and so on. All these songs have long existed in the cultural field, all successfully exploiting black imagery — from tragedy and demonic possession to carnival.

I wanted to assemble this black choir into a single album by running it through myself, through my own reception of it. Technically, it’s a series of covers or re-imaginings: sometimes I tried to stay close to the original (which still didn’t work), but in most cases almost nothing of the source material remained. Partly because the model won’t let you write „please give me a cover of Gainsbourg’s Black Trombone in the style of Peste Noire“ — you have to describe what matters: the dirt, the tempo, the vocal manner, the structure of the riffs, the colour of the distorted guitars, the overall mood, and so on.

The result is a pretty strange object: familiar songs that sound like an alternative branch of pop-music history where everything went slightly off course.

And of course this is where questions of authorship and ethics become particularly sharp: where do quotations end and «your own» begin? Sampling in hip hop seems more or less normalized and legitimized, but do I personally have the right to turn «Dark Eyes» into avant-garde black metal? Who does that result belong to — me, the algorithm, the original authors, or all of us at once?

My answer: I don’t know. The question bothers me, but it doesn’t paralyze me. In any case, it turns out you can’t put this album on streaming platforms for copyright reasons, so that solves that problem.

My latest completed large-scale project, Conclave Obscurum, is also built on a weird time loop. Back in 2004 I had a Flash installation with the same title. It lived in a browser and functioned as a piece of zero-content net art where I tried to merge gothic pathos with cheap horror and early-2000s web aesthetics.

Twenty years later I return to that title and those images — and to music that back then was simply beyond my reach. Now I have Suno, Audition, access to other people’s and my own references, and twenty extra years of obsessive listening under my belt.

Some of the tracks on Conclave Obscurum are based on music by other people — I say that explicitly in the liner notes: there’s Alexey «hiddenkid» Bazunov, who originally wrote music for that project, there’s Georgy Sviridov, Serge Gainsbourg, Coil, Rompeprop, Sopor Aeternus. The rest is mine. All the programming, arranging, mixing, mastering, and the cover art are mine as well. In genre terms, the record hovers somewhere between neoclassical avant-garde, gothic, progressive black metal, dark jazz, and dark ambient. In my inner sense, though, it’s another musical ritual of reconstructing myself and my vanished youth. In that sense it’s probably my most «human» album, because here AI works not as an author but as a tool for reminiscence and reflection.

Suno has gone from a simple «write me a song in the style of…» generator to a fairly complex instrument where the structure of the prompt matters, as do the lyrics field and a real understanding of the model’s limitations.

At some point I realized I was not only writing songs but also developing a language for talking to the model. Essentially, a weird dialect of machine English is emerging, translating my gut feelings into instructions. A typical Suno prompt of mine looks something like this:

Genre: not just «black metal, ” but avant-garde dissonant black metal song, fused with dark trip-hop and dark jazz.

Key: in A minor, use a strict repeating 4-bar chord progression for all main distorted guitars and bass riffs: | Am | Am (b5) with a flattened fifth (A minor with Eb in the chord) | B7b9 | E7b9 | (repeat), tritone-heavy.

Rhythm: use the uploaded audio as the strict rhythmic reference, odd meter: 13/8 (grouped 3+3+3+4), feels like a 6/8+7/8 waltz, keep 13/8 throughout, avoid ¾ and 4/4, tempo ~94 bpm, no backbeat on 2 & 4, shaker on straight 8ths; kick on 1, 4, 7, 10; gentle push on 11.

Structure: bass outlines roots at group starts, no catchy riffs, only jagged dissonant clusters, no chorus, no hooks.

Instrumentation: main focus: painful sandpaper-abrasive low-tuned distorted guitars, tremolo riffs, chaotic but precise drums, deep bass rumble, ritual harsh male growling vocals plus distant Slavic funeral-lament voices, with Slavic flutes and jaw harp as haunted textures.

Production: suffocating-style production, claustrophobic mix, guitars as a narrow wall of noise.

Mood: heavy horror-industrial vibes, haunted textures, mood of metaphysical dread, unstable, no catharsis.

The lyrics field is a separate story. Many Suno users use the Lyrics box not just for the actual text of the song but also for extra instructions, references, rhythmic patterns, and so on.

After that, the grind begins. The first generation almost always misses the point, and I start looking for ways to be more articulate about what I want. For example, if Suno spits out something too pop, I radicalize the language: instead of just «dark» I write «lo-fi, raw, distorted, dissonant, underproduced.» If the vocals are too clean, I add «harsh hoarse distorted vocals, low-pitch male guttural growling and screaming, weary and drunk, Mongolian throat singing» and then sift through for the least offensive results.

When people hear «AI made music for me, ” they tend to picture something like: I typed one line, hit a button, and had a finished release thirty seconds later.

It’s more complicated than that. In reality, as I described above, my process looks like this: first I generate a lot of variants with different prompts and settings — adding words like „raw, ” „underproduced, ” „dissonant, ” „whispered harsh vocals, ” „tape hiss, ” tweaking Weirdness and Audio Influence, trying out different Personas (I’ve collected a few dozen).

At that stage the neural net stops being a magical creature with „non-human subjectivity“ and turns into a very patient but somewhat dim musician you have to brief a hundred times about what exactly is driving you crazy: „make it dirtier, ” „lose that heroic build-up, we are not scoring a Marvel movie, ” „give me the feeling this was recorded in a hut in a Norwegian forest, not at Vasya Vakulenko’s Gazgolder studio.“

Out of a hundred generations I might pick five and download them (sometimes as separate stems). In Adobe Audition I cut and splice the best bits: a verse from one version, a chorus from another, an atmospheric intro from a third, a nicely articulated word from a fourth, a solo from a fifth.

The next circle of hell is mixing and mastering. The routine is usually like this: having assembled a composition in Audition from pieces of different generations, set up the crossfades, and cleaned away obvious artifacts, I ask ChatGPT: what’s the best way to master, say, avant-garde dissonant black metal in the manner of Deathspell Omega? It explains. I build an FX stack (it used to be just Audition’s native effects; lately I’ve fallen in love with Ozone 12 Advanced).

I make a test mixdown and run analysis: spectrum, Amplitude Statistics, true peaks, average loudness — all that beautiful, frightening stuff. I describe the picture to ChatGPT, sometimes sending screenshots, sometimes just complaining in words that I hear, say, a muddy midrange, overloaded lows around 60–80 Hz, and «sand» up in the 3–4 kHz area.

The model replies in real time like a very decent audio-engineering instructor: try pushing the vocal back a bit; ease up on the compressor; widen the stereo image on the highs and tighten the bass; go easy on the limiter. I tweak the settings, run the analysis again, report back. The whole scene is quite comical: a non-musician arguing with a text robot about how best to increase the dynamic range of a track generated by yet another model.

The result is almost certainly not a «perfect master.» But I’m satisfied with the very figure of the human between two AIs, moderating their conflict in line with his own taste. Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called the children of God, right?

Where is «the musician» in this entire construction? Is there one at all?

If you look at it through the eyes of someone who went through music school, conservatory, rehearsals with live bands, studio grind, my practice probably looks like this: dilettante, generative AI, plug-ins, and, as the cherry on top, another AI acting as a consultant. That alone is enough to make someone say: «Right, so this isn’t music, it’s content.»

I fully understand that reaction. But I’ve never related to generative tools as a mere toy — «we pressed a button, had a laugh, and forgot about it.» I have decades of melomania behind me, old lyrics, a failed band from the nineties, a love of black metal and Angelo Badalamenti. The «push-button» model simply doesn’t work for me.

I don’t see a «composer» or «arranger» in Suno, and I don’t see a «musician» or «sound engineer» in myself. What I see is a distributed organism where:

model developers set huge libraries of sound and statistics in motion;

training datasets carry the shadows of real musicians;

algorithms propose variants in which both other people’s styles and the system’s own limitations are audible;

I bring my lyrics, concepts, and taste filters to the ritual;

listeners (if they exist) bring interpretations, emotions, irritation, sometimes support.

For me Roland Barthes and his «Death of the Author» feel very relevant here. The author doesn’t literally die, but he ceases to be the axis around which everything revolves and becomes one actor among many in the network — important, but no longer central.

For quite a while I didn’t explicitly say in public that my albums were made with AI (relying on the fact that from the sound and from my social-media posts it was reasonably obvious). In the Bandcamp credits I wrote: humanimalien — lyrics, programming, arrangements, mixing, mastering. When people asked in the comments who played the violin part, I replied: «the angels.»

Now I’m inclined to see that omission as an ethical blind spot, which is precisely why I think it’s important to say it aloud (when asked): yes, there are AI models involved; yes, all this is built on enormous archives belonging to other people; yes, legally and morally there’s a lot of grey area here.

At the same time I deliberately do not monetize these releases. This is not a business and not a «quick way to blow up on Spotify.» It’s an artistic, research, and therapeutic project. Does the musician disappear? In the old sense — yes, undeniably. Instead of the sovereign figure of «the author of everything, ” we get a curator, a music glutton, an editor, a programmer of affects who works not only with people but also with machines.

There is another audience that matters to me — students. The problem starts if, after hearing this story, someone says: «Oh, so you don’t need to learn to play to make albums. I’ll just go and press a couple of buttons.»

Here I’d like to say two things.

First, without deep listening and a certain level of melomaniac literacy, this all turns into a factory that churns out disposable AI slop. If you can’t hear the difference between atmospheric black and DSBM, if you don’t understand when your compressor has turned the mix into a cement block, if you can’t feel the dramaturgy of a track, then the neural net will only amplify your deafness.

Second, AI music-making for me is an experiment and a form of study, not a profession, and I have no desire to claim the identity of «musician.» I’m interested in the process and pleased with the result; as Egor Letov wrote: «…if what you’ve created doesn’t make you yourself go mad and rave with delight, then it’s all just vain, transient bullshit.» It’s both a virtual laboratory — where in one evening you can do what would take a live band months — and, at the same time, an unusually efficient practice of self-reflection and self-therapy. A deeply individual practice, too, because in the end «death is a lonely business.»

There’s a popular scenario: in a couple of years generative models will become so efficient that anyone will be able to assemble a perfectly produced album in ten minutes — the fantasy of an endless Spotify where everything is tailored to you.

If that happens, my current releases will look like archaeology. That’s fine, because I’m not erecting a monument to myself; I’m keeping a diary. It’s a record of how a person with no musical education but with clinical melomania tried to negotiate with machines about his ideal album — and to find out what remains once «the musician disappears.»

The questions will stay the same: why do I need music at all; what exactly do I hear in the things I like; who am I talking to when I write the text of an «Akathist» or turn a «cruel romance» into black metal; and so on. In this story, neural networks are simply a very strong magnifying glass, one that enlarges both my strengths and my weaknesses, finds moves I would never have thought of on my own given my musical ineptitude, and lets me experiment a lot, fail loudly, and learn from the wreckage — which is always good for the soul.